Poole's Cavern has been the subject of much curiosity and interest by travellers and antiquarians over the past 350 years, but it was not until the middle of the 19th century that anybody realised that the cave contained archaeological remains.

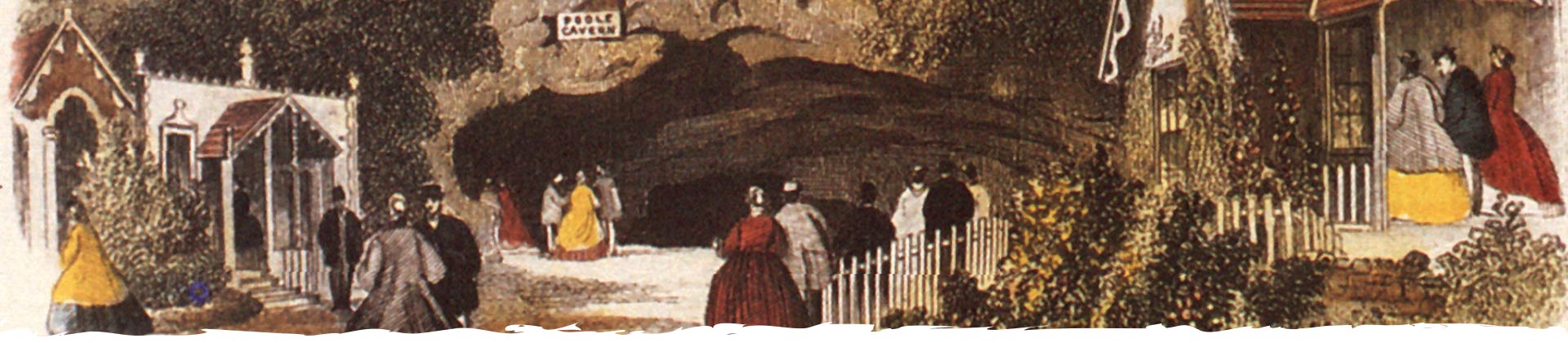

Discoveries were first made when the cavern was opened as a showcave in 1853. The glacial sediment was dug out of the cavern entrance and human and animal bones were unearthed. These finds were acquired by the famous barrow digger Thomas Bateman.

Whilst these remains provided little information to archaeologists, much more spectacular finds were made by Frank Redfern, custodian and guide who, in 1865 began to excavate beneath a layer of stalagmite within the cave. He unearthed animal and human remains in the stalagmite layer itself plus some Roman coins, samian ware pottery and a bronze brooch inlaid with silver. All these finds were installed in a museum at the cavern entrance.

Prehistoric Remains

Among the finds made in the cavern in the late 19th century were some crude decorated fragments of pottery which were recognised as being of pre-Roman date and indeed further fragments have been found.

On the hillside above the cavern, flint and stone artefacts dating from the late Neolithic period (around 2000 BC) and early Bronze age (around 1500 BC) are not uncommon, indicating that these prehistoric peoples were active in the area.

Stone axes used by Neolithic farmers to fell trees are particularly common around the Buxton region, and there are examples from the vicinity of Poole's Cavern made of stone types traded from centres as far apart as Cumbria and Cornwall.

On Grinlow, above the cavern itself, Solomon's Temple is sited upon a prehistoric barrow grave which was excavated before the tower was built. Several crouched human burials were found, together with cremated human remains, a decorated food vessel, flints and animal bones, all indicating an early Bronze Age date.

The Finds

By far the most abundant of the excavated remains were fragmented bones and teeth of animals including cattle, sheep, pigs, brown hares, domestic fowl, fish, oysters and cockles. Most of these were probably food remains and are typical of other Romano-British sites in the Peak District. A number of pieces of the bones found had been fashioned into utensils such as handles and needles, and a number of human bones and teeth were also found.

The most spectacular and interesting artefacts are numerous metal objects of bronze, lead and iron, which provide the most substantial evidence as to the use of this cave in Roman times.

Items of bronze jewellery were especially plentiful including enameled brooches, disk brooches, dolphin and trumpet style brooches, rings, earrings, decorated studs. Some brooches were made of iron and lead. A possible explanation for this extraordinary assemblage of metalwork is provided in the numerous finds of metal associated with the metalworking process.

Bronzesmith at Work

We know that much bronze jewellery is of British origin, but very few sites in Britain have yielded any evidence of jewellery metalworking.

It seems very likely that a bronzesmith was based at the cavern in the early second century, probably living and working just outside the cave, whilst storing materials inside. His trade would have fulfilled an important role next to the Roman army in Buxton, whose own metalworkers would have been solely engaged in producing military hardware, and he would doubtless have been relatively wealthy, possible undertaking ancillary trade in wine (hence the amphorae).

Throughout the Roman occupation Buxton was part of a military zone, so anyone not attached to the army and trading valuable goods may well have felt vulnerable. The solution may have been to base the trade next to a 'safe house' such as the cavern. The location may also have had religious significance.

Evidence of Metalworking

Although there is ample proof of general activity in Poole's Cavern at earlier and later dates, there is substantial evidence of metal working in the second century AD during the Roman occupation.

This includes unworked bronze; a hammered bronze ingot, rod and sheet and objects associated with the casting process. Of the latter, one bronze brooch was found with untrimmed flashing still attached, and an identical lead counterpart was found which may have been the handmade model used to make a clay mould for casting. The Victorian collection once included a crucible from the cavern, which supports this theory.

In terms of their style, all the brooch types can be accounted for within the period AD 100 - 150, and these dates generally coincide with most of the pottery types found, which include some sophisticated wares such as Samian and amphorae (wine jar) fragments. Coins were also more common within these date ranges.