Visitors to Poole's Cavern have often put pen (or quill) to paper describing their underground adventures. Here are a sample of some of these passages dating back to the 1600s.

From A. Jewitt's 'History of Buxton' (1911)

"Poole's Hole, a cavern in the side of Grinlow, though possessing more of the terrific than the picturesque, has been considered by visitors one of the greatest curiosities of Buxton. It is one of those frightful chasms in the side of the limestone rock, that no man would dare enter from curiosity only, were he not assured that the visit to this souterrein would gratify his senses in beholding what he could never hope to see on the surface of the earth. Many of our writers have described, and most of them fill it with wonders, with flitches of bacon, columns of stalactite, lions, bears, wolves, mice, etc. But few of them have described it as it really is, a 'Cavern of Horrors,' from which the more resolute, however strong their curiosity, gladly return to the precincts of the day; and from whence the timid scarcely dare hope ever to emerge."

An unknown 18th Century travellers impression of "dreary" Buxton

"Our proximity to Pool's Hole was a sufficient temptation to visit the celebrated cavern. It's aperture is at the foot of a mountain and so narrow at the first entrance as hardly to admit a person without much difficulty of stooping.

"Our guides were all females, who by their dress and looks, recalled to memory every picture of the midnight hags as represented in the Drama [Macbeth].

"Their address to each other was unintelligible to us, and seemed to constitute a distinct language, for their provincial accent was not barbarous."

Mr. JT Millett's 'A Wanderer Looks Back' from the Buxton Advertiser (1949)

"How well one recalls 'Warslow' Joe the guide, with his six-foot wand or broomstick bearing on its tip a lighted candle; how he would go around calling out and gathering his 'flock' for the cavern and its hidden mysteries. It has often been a source of wonderment to me how Joe managed to escape chronic rheumatism, for he practically lived in that damp cavern - a veritable troglodyte - only going home to sleep.

"The number of journeys he made along those subterranean marble halls during his life would run into thousands of miles, and the 'tips' that fell into his supplicating cap at the end of each journey would amount to hundreds of pounds.

"Dear old Joe! Gone from us now many years. Let us hope he is resting far, far away from caverns and such inferno-like places."

From Art Hacker's 'Buxton Thro' Other Glasses' (turn of the century)

"We will now proceed to explore Poole's Cavern. Certain preliminaries are necessary in most undertakings, and in this case you should go provided with your second-best clothes only, a pair of serviceable boots, a little loose change, and a receptive mind.

... A kind of abandon-hope-all-ye-who-enter-here sort of feeling assails you as you pass beneath the low arch of rock, but the confident air of the guide reassures you.

... One word of warning as you enter.

Do as the guide tells you, from his first thoughtful words, 'Mind your head,' onwards.

His early solicitude for your hat might change to complete disregard for your person if you angered him when he had you safe in the bowels of the hill and turned the lights out. History records dark deeds perpetrated in the ancient stronghold of the robber Poole. Don't let it occur again."

From Art Hacker's 'Buxton Thro' Other Glasses'

"Tis an awesome thought. Some time ago, this scientific shower bath was turned on, and, continuing instant in the work, indefatigable through unnumbered centuries, formed with infinite patience the panorama of wonders it is now in these latter days your privilege to ignorantly admire. Observe, mark, and learn, and inwardly digest.

... Here, also, you renew aquaintance with the river Wye, which, if an infant when it reaches the Gardens, is now but a babe in swaddling clothes, perpetually christened by the falling drops and hushed to crooning slumbers by the still embraces of the over-arching grandeur.

It makes a chap feel how very unnecessary and unimportant his pygmy presence is upon this planet when he realises that if he sat within the cave... for the whole of mortal man's allotted span and more, he could not raise a stalagmite the size of a shilling. And some people's lives do not realise so much after funeral expenses are paid."

From Art Hacker's 'Buxton Thro' Other Glasses'

"... here a roaring torrent bids you stand,

Forcing you climb a rock on the right hand,

Which hanging, pent-house-like, does overlook

The dreadful channel of the rapid brook,

So deep, and black, the very thought does make

My brains turn giddy and my eyeballs ache."

J.T. Millett's 'A Wanderer Looks Back' from the Buxton Advertiser (1949)

"... right in the heart of the old town there is a timepiece that has been ticking away the minutes, hours and days for not only hundreds of years, but thousands, and I wonder how many Buxtonians know it? Familiarity certainly breeds contempt...

"... beyond a small percentage of professors, savants and students I don't suppose more than five percent of the multitude who had seen that comparatively ageless natural plinth of calcium carbonate that stands within those gloomy portals gave more than two thoughts about it.

"They just gathered round and in the damp sunless shadows listened to the description from 'Warslow' Joe delivered in his old sing song style - so well remembered - and all they retained about it was its trite title the 'Beehive' [the Font]. It is highly probable that they thought the 'poached eggs' a little farther along, far more interesting and certainly more amusing.

"Yet surely here was - and still is - one of the most remarkable monuments to the immensity of time that one could ever wish to see; here indeed is one of the world's oldest timekeepers.

"... The whole of this mass has been built up by tiny drops of water, each drop depositing a minute quantity of calcium carbonate, and each drop falling from the great carboniferous roof overhead a little faster in the winter than in summer, but always so many to the minute and dead on time in each period. I remember once taking my watch and timing it but have now forgotten how many to the minute. Perhaps the present proprietor will kindly give us the correct figures.

"Natures marvellous timepiece, to which the human span of three score years and ten is just nothing. Centuries before the hour glass of sand or the sun dial and the mechanical clocks of the toothed-wheel type appeared, the ancient Egyptians took the tip from nature and used what they called the 'water clock' or clepsydra, which appeared to consist of a graduated cylinder filled with water, which escaped a drop at a time through a small hole at the bottom.

From Ben Rose's 'Guide to Buxton'

"We next enter a spacious vaulted chamber, where the roof is lofty, and the dripping walls are in part adorned with beads and moulding, and draped and festooned with crystallized incrustations of unsullied whiteness. Stalactites of various shapes and dimensions depend from the jutting rocks, each dignified by a particular name; some are clustering together in groups, others hang in spiral convolutions from the roof, and others again assume all sorts of fanciful and picturesque forms, their filmy sides resplendent with the brightness that gleams and sparkles upon every rippling curve and inequality. The guide calls each by name: the Rhinoceros, the Bee-hives, the Oyster-beds, and so on through the entire catalogue; then he explains the process of formation, and tells you that for variety and beauty of decoration there is no cavern in the kingdom can compare with this subterranean temple."

From Daniel Defoe's 'Tour of Britain'

"Dr. Leigh spends some time in admiring the spangled roof. Cotton and Hobbes are most ridiculously and outrageously witty upon it. Dr. Leigh calls it fret work, organ or choir work. The whole of the matter is this, that the rock being every where moist and dropping, the drops are some fallen, those you see below; some falling, those you have glancing by you, and other pendent in the roof. Now as you have guides before you and behind you, carrying every one a candle, the light of the candles reflected by the globular drops of water, dazzle upon your eyes from every corner; like as the drops of dew in a sunny-bright morning reflect the rising light to the eye, and are as ten thousand rainbows in miniature; whereas were any part of this roof or arch of this vault to be seen by a clear light, there would be no more beauty on it than on the back of a chimney; for, in short, the stone is coarse, slimy, with the constant wet, dirty and dull; and were the little drops of water gone, or the candles gone, there would be none of these fine sights to be seen for wonders, or for the learned authors above to show themselves foolish about.

"Let any person therefore, who goes into Poole's Hole for the future, and has a mind to try the experiment, take a long pole in his hand, with a cloth tied to the end of it, and mark any place of the shining spangled roof which his pole will reach to; and then, wiping the drops of water away, he shall see he will at once extinguish all those glories; then let him sit still and wait a little, till, by the nature of the thing, the drops swell out again, and he shall find the stars and the spangles rise again by degrees, her one, and there one, till they shine with the same fraud, a mere deceptio visus, as they did before."

From Charles Cotton's 'The Wonders of the Peak' (1683)

"Over the brook you're now obliged to stride,

And, on the left hand, by this pillars side

To seek new wonders, though beyond this stone,

Unless you safe return, you'll meet with none,

And that indeed will be a kind of one:

For from this place, the way does rise so steep,

Craggy, and wet, that who all safe does keep,

A stout, and faithful genius has, that will

In hells black territories guard him still;

Yet to behold these vast prodigious stones,

None who has any kindness for his bones,

Will venture to climb up, tho' I did once,

A certain symptom of an empty sconce;

But many more have done the like since then,

That now are wiser than to do it again.

Having swarmed sevenscore paces up, or more

On the right hand you find a kind of floor,

Which twining back, hangs o're the cave below,

Where, through a hole, your kind conductors show

A candle left on purpose at the brook,

On which, with trembling horror, whilst you look,

You'll fancy from that dreadful precipice,

A spark ascending from the black abyss.

Returning to your road, you thence must still

Higher, and higher mount the dangerous hill,

Till, at the last, dirty, and tired enough,

Your giddy heads do touch the sparkling roof.

From Charles Cotton's 'The Wonders of the Peak' (1683) (continued)

And now you here a while to pant may sit,

To which adventurers have thought requisit

To add a bottle, to express the love

They owe their friends left in the world above.

And here I too would sheath my wearied pen,

Were I not bound to bring you back again;

You therefore must return, but with much more

Deliberate circumspection, than before:

Two hob-nail Peakrills, one on either side,

Your arms supporting like a bashful bride,

Whilst a third steps before, kindly to meet

With his broad shoulders your extended feet,

And thus from rock to rock they slide you down,

Till to their footing you may add your own:

Which is at the great torrent, roars below,

From whence your guides another candle show

Left in the hole above, whose distant light,

Seems a star peeping through a sullen night."

From an anonymous writer around 1710

"When you are entered about eight yards the hollow suffers you to rise, and view the beauty of the arched roof above, which shines as if 'twas beset with stars."

From Michael Drayton's Poly-Olbion (1622)

"[The] entrance though depressed beneath a mountain steep,

Besides so very straight, that who will see it must creep,

Into the mouth thereof, yet being once got in,

A rude and ample roof doth instantly begin

To raise itself aloft, and who so doth intend

The length thereof to see, still going must ascend

On mighty slippery stones, as by a winding stair,

Which of a kind of base dark Alabaster are,

Of strange and sundry forms, both in the roof and floor,

As nature showed in thee, what ne'er was seen before.""My pretty daughter Poole, my second loved child,

Which by that noble name was happily enstilled,

Of that more generous stock, long honoured in this shire,

Of which among the rest, one being outlawed here,

For his strong refuge took this dark and uncouth place,

An heirloom ever since, to that succeeding race."

From Charles Cotton's 'The Wonders of the Peak' (1683)

"The first [wonder] I meet in my way,

Is a vast cave, which the old people say,

One Poole an outlaw made his residence;

But why he did so, or for what offence,

The beagles of law should press so near,

As, 'spight of horrors self, to earth him there,

Is in our times a riddle; and in this

Tradition most unkindly silent is:

But whatsoe'er his crime, than such a cave

A worse imprisonment he could not have."

From Daniel Defoe's 'Tour of Britain' (1731)

"The story of one Pole or Poole, a famous giant or robber, (they might as well have called him a man-eater) who harboured in this vault, and whose kitchen and lodging, or bedchamber, they show you on your right-hand, after you have crept about ten yards upon all-four; I say, this I leave to those who such stories are better suited to, than I expect of my readers."

From Daniel Defoe's 'Tour of Britain'

"It is a great cave, or natural vault, ancient doubtless as the mountain itself, and occasioned by the fortuitous position of the rocks at the creation of all things, or perhaps at the great absorption or influx of the surface into the abyss at the great rupture of the earth's crust or shell."

"It may be deepened and enlarged by streams and eruptions of subterraneous waters, of which there are several, as there are generally in such cavities."

From Daniel Defoe's 'Tour of Britain'

"Masses of rock are thrown about in every direction, and piled one upon another in a diversity of forms rugged chaos... A crystalline stream is seen channelling its way through the gloomy chasm, twisting and turning among rude blocks of limestone as it courses on; the water is strongly impregnated with lime, and leaves a deposit upon the birds' nests and other objects which are placed in it to undergo the process of incrustation. Huge masses of stalactite adhere to the walls, their surfaces roughened with countless crystallized conformations where the moisture has trickled over them for successive ages; curious growths of stalactites hang pendent from the roof and from every jutting fragment and inequality, and you pause to witness the effect as the light flashes and glitters upon their snowy shapes. The damp trickles through in places, and falls to the ground with continuous patter that awakens the sullen echoes of the mountain, and adds to the impressiveness of the scene. Stalagmite grow upon the floor and ledges of the rock, fashioning themselves into various grotesque and uncouth shapes, which fancy has endeavoured to liken to the several objects whose names they bear, though it must be confessed that the resemblance is oftentimes remote indeed."

From an anonymous writer around 1710

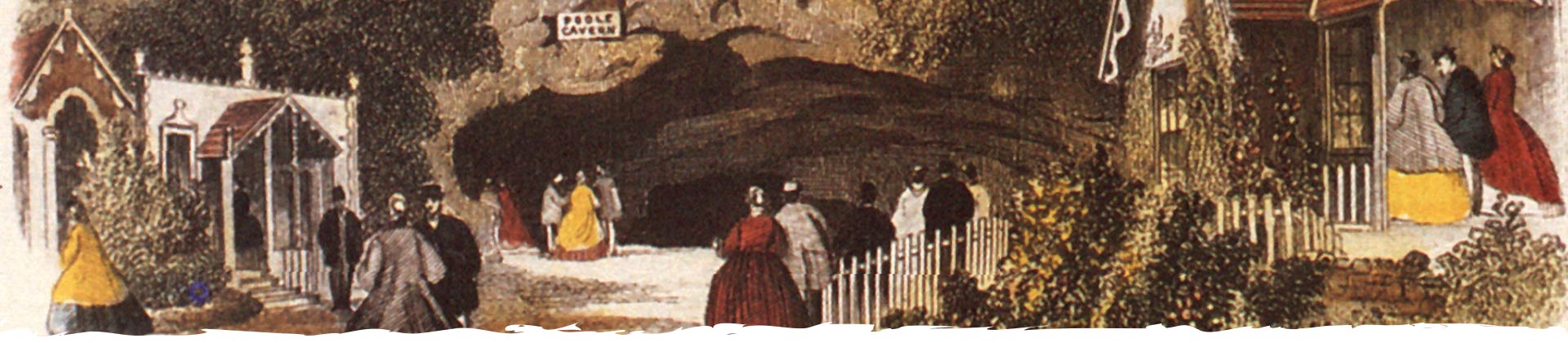

"A few years later the cave came into the hands of an enterprising tenant, Francis Redfern, stonemason and builder, who made the paths smoother, cleaner and safer, the entrance easier, and, as soon as gas was available, had the cave lighted with gas, probably the first natural cavern to be so lighted. Incidentally, of course, he made what had apparently been an exciting and even dangerous adventure into what was merely an interesting and safe walk underground, and he tried to add to its attractions. In 1860 he advertised that it was 'illuminated at all hours of the day with 130 gas lights,' and that there was a band in the interior of the cavern twice a week. Redfern also made excavations, the results of which, with many unrelated and incongruous curiosities, are shown in a museum built near the entrance to the cavern."

From Ben Rose's 'Guide to Buxton'

"The darkness... is not so apparent as in other caverns of the Peak, the interior being well lighted with gas, a modern innovation which but ill affords with the natural features of the place, and which detracts somewhat from the effect, for every hollow and recess being illuminated, there is no room for the imagination to wander, and we lose that idea of vastness and profundity which a shadowy obscurity is so calculated to convey."

From Charles Cotton's 'The Wonders of the Peak' (1683)

"Did not sometimes the curious visitors,

To steal atreasure, is not justly theirs,

Break off much more at one injurious blow,

Than can again in many ages grow.""And this forsooth the Bacon-Flitch they call,

Not that it does resemble one at all,

For it is round, not flat: but I suppose

Because it hangs i' th' roof, like one of those,

And shines like salt, Peak Bacon-eaters came

At first to call it by that greasy name."

J.T. Millett's 'A Wanderer Looks Back' from the Buxton Advertiser (continued)

And here in the old town is a timepiece that was ticking off the hours thousands of years before the 30th century B.C. when the Egyptians built the great pyramid, and if the activities of the Grin Low quarrymen or the building of the Stanley Moor reservoir have not interfered with the hydraulics of Poole's Cavern, it is still going dead on time.

"During the last fifty odd years the deposit of calcium built up by those drops of water is probably little more than the thickness of, say, one quarter of an inch, and there are some ten vertical feet of it, to say nothing of the cubic feet. At this rate of growth, human history alongside the antiquity of this monolith is just a mere flash in time. When Copernicus was formulating his famous planetary theory over five hundred years ago, it was taking the falling drops of water with chronic exactitude.

"Let us even go back to the era of Roman Buxton - A.D. 47, the old Aqua of Trajans days, when Buxton was definitely established under Roman arms. There in the darkness, it was still going about its business - drip! drip! drip! It is possible an odd cohort from the emperor's legion forced their way through the one-time difficult entrance to the vaulted chambers of Buxton's natural wonder, there to gaze, under the glare of the torch, at this remarkable piece of calcium and its descending beads of calcined water relentlessly ticking off the minutes with the regularity of a clock.

"That would be getting on for nearly two thousand years ago, and to think this stalagmitic mass was even then only some twelve inches shorter than it is today.

"The next time you visit Poole's Cavern take a good look at it, look down it's wet surface, rippled and scored like the hide of an old mammoth, as it rises from the bed of the river Wye. You will be looking at something that is probably fifteen thousand years old."

From Charles Cotton's 'The Wonders of the Peak' (1683)

"The fairest, brightest Queen, that ever yet

On English ground unhappy footing set,

Having to the rest of the Isles eternal shame,

Honour'd this stone with her own splendid name.

For Scotlands Queen, hither by art betrayed,

And by false friendship after captive made,

(As if she did nought but a dungeon want

To express the utmost rigor of restraint)

Coming to view this cave, took so much pains,

For all the damp, and horror it contains,

To penetrate so far, as to this place,

And seeing it, with her own mouth to grace,

As her non ultra, this now famous stone,

By naming, and declaring it her own;

Which, ever since so gloriously enstalled,

Has been the Queens of Scot's her pillar called."

From Daniel Defoe's 'Tour of Britain'

"It is a piece of stone like a kind of spar, which is found about the lead; and 'tis not improbable in a country where there is so much ore , it may be of the same kind, and, standing upright, obtained the name of a pillar; of which almost every body that comes there, carries away a piece, in veneration of the memory of the unhappy princess that gave it her name. Nor is there anything strange or unusual in the stone, much less in the figure of it, which is otherwise very mean, and in that country very common.

"... In short, there is nothing in Poole's Hole to make a wonder of, any more than as other things in nature, which are rare to be seen, however easily accounted for, may be called wonderful."

From Ernest Axon's 'Historical Notes on Buxton its Inhabitants and Visitors." (1945)

"It was with some difficulty we prevailed with our guides to a further search, the way being very dangerous. At last they yielded to lead us by arm down a steep and slippery descent by the side of the Pillar. When we came to the bottom we crossed a dangerous stream, jumping from one stone to another, till we came to the foot of the most affrighting rocks that ever we beheld. Our next attempt was to storm this place, which we did by laying hold on the rugged parts of the solid with our hands, while our guides supported us behind. After we had ascended about one hundred yards our heads almost touched the roof, and looking down we saw a candle left at the stream below which looked like a distant star."

From Ben Rose's 'Guide to Buxton'

"Here the passage seems to terminate in a cul de sac; but, on looking round, a steep and rugged incline is seen leading up over disjointed rocks and slippery crags to a considerable altitude, and terminating in a narrow opening, through which a person may contrive to pass by crawling on his hands and knees. This opening forms the entrance to a range of caverns, which are believed to ramify and extend in various directions. The guide clambers up and puts his head through, but having already satisfied our curiosity, we feel no inclination to follow his example."